Blood on the Battlefield: How World War II Revolutionized Transfusion Medicine

The story of how global warfare revolutionized blood preservation and saved countless lives.

by Shanise Keith • September 16, 2025

It's 1940, and German bombers are pounding London night after night. Hospital emergency rooms are overflowing with civilian casualties, but there's a critical shortage. Not of doctors or beds, but of blood. For the first time in history, blood was about to become the most precious currency on Earth.

By the war's end, over 13 million pints of blood had been collected by the American Red Cross alone. Mobile "bloodmobiles" were racing across continents. Blood was being flown from the mainland United States to Pacific islands thousands of miles away. What had been experimental medicine in 1939 became standard medical practice by 1945.

This is the story of how World War II transformed blood from a medical curiosity into the foundation of modern transfusion medicine, and how the heroes behind this revolution established every protocol we follow today as phlebotomists.

Setting the Stage: Blood Before the War

To understand the magnitude of World War II's blood revolution, we need to appreciate how far medical science had come, and how far it still had to go. British physician William Harvey's discovery of blood circulation in the 1600s had eventually led to the first successful human-to-human transfusion by British obstetrician James Blundell in the 1800s for treating postpartum hemorrhage.

The real breakthrough came when Karl Landsteiner discovered the first three human blood groups, making safe transfusions possible by ensuring compatibility. But even by 1914, blood transfusions were dangerous, direct procedures that had to happen immediately from donor to patient.

World War I changed everything. The carnage of that conflict drove rapid advances in blood preservation and transfusion techniques. Canadian military doctor Lawrence Bruce Robertson began performing "indirect" blood transfusions on the Western front in 1917, creating the first battlefield blood banks. The first successful transfusion from this early blood bank model took place in 1917, proving that blood could be stored and transported to save lives.

By the 1930s, researchers like Dr. Charles Drew were perfecting blood preservation techniques. Much of Drew's research focused on one of the most challenging medical problems of that time: how to "bank" blood so it would be available for transfusions as needed. Before World War II several researchers had discovered that sodium citrate would keep the blood from clotting, and that dextrose would preserve it for up to two weeks under refrigeration.

But nothing could have prepared the medical world for what was coming.

Blood for Britain: When Blood Became International Currency

As the Blitz intensified in 1940, Britain faced an unprecedented medical crisis. The bombing campaigns were producing massive civilian casualties, but Britain simply didn't have the infrastructure to collect and process enough blood on its own.

Enter "Blood for Britain," a program that would transform international medical cooperation forever. For the first time in history, American donors were literally giving their blood to save British lives an ocean away. This wasn't just medical aid; it was blood functioning as international currency.

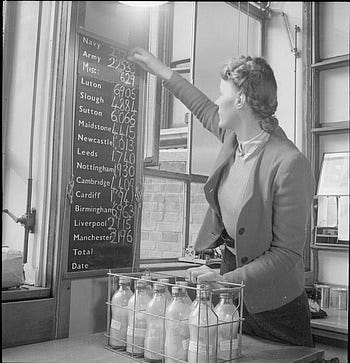

Army Blood Transfusion Service: Refrigerated blood supplies arriving at a Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) in France in January 1940. Field Transfusion Units (FTU) worked with Casualty Clearing Stations and Field Dressing Stations (FDS) and were supplied from a central bank which collected blood from donors.

Charles Drew, an African American physician and surgeon, was appointed medical supervisor for the program. His impact was immediate and revolutionary. Drew developed mobile blood donation stations (the first "bloodmobiles") and created the first successful mass production technique for blood processing.

The real innovation was in preservation and transport. Drew's team developed dried plasma packages that came in two tin cans: one bottle contained distilled water, the other contained dried plasma. In about three minutes, the plasma would be ready to use and could stay fresh for around four hours. For the first time in history, blood was being processed on an industrial scale with standardized procedures, quality control, and mass distribution networks.

The British Revolution: Centralized Blood Banking

While Americans were shipping plasma across the Atlantic, Britain was developing what would become the most sophisticated wartime blood banking system in history. The British approach was revolutionary: instead of bleeding troops at the front lines (as Americans and Germans did), they supplied military personnel with blood from centralized depots.

This centralized system allowed for better quality control, more efficient distribution, and crucially, it meant that healthy soldiers weren't weakened by blood donations at the front lines. The numbers tell an incredible story of success: over 700,000 British donors were bled over the course of the war, and the system proved so effective that it evolved into the National Blood Transfusion Service in 1946. This was the first national blood service ever implemented.

American Transformation: From Skepticism to Success

American military medicine initially resisted battlefield blood banking. There was skepticism about whether blood could maintain its effectiveness over long distances and whether the logistical complexity was worth it. But as American forces saw the British success, attitudes changed rapidly.

The transformation was dramatic. The Red Cross collected more than 13 million pints for the military, the largest coordinated blood collection effort in human history. Mobile bleeding units were deployed everywhere, even to disciplinary stockades to collect from prisoners who couldn't report to donor centers.

In the Mediterranean region, the statistics were staggering: about 70 percent of field hospital casualties required blood and received an average of 3 pints each. Field hospitals were supplied with all the blood they requested. They were never expected to provide their own. As the fighting moved north through Italy, bleeding centers were established in Rome, Florence, and Pisa, creating an unprecedented medical supply chain.

Innovation Under Fire

The pressure of wartime led to rapid technical innovations that would define modern blood banking. Allied medical forces were issued standardized transfusion kits that allowed doctors to administer blood to injured patients even before transferring them to casualty clearing stations.

Quality control advanced rapidly under wartime pressures. ABO blood-typing and syphilis testing was performed on each unit of blood, establishing safety protocols that became standard worldwide. The war also accelerated advances in anticoagulant and storage techniques, all vital elements for effective and safe blood banks.

The Pacific Challenge: Blood Across the Ocean

The Pacific region presented unique challenges. The vast distances, tropical climate, and island-hopping campaign made blood preservation and transport incredibly difficult. The solution was innovative and dramatic: blood was flown from the mainland United States to Pacific island bases, perhaps the most striking example of blood as strategic military currency in the entire war.

Advanced Base Blood Bank facilities were established on islands like Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Each facility had to be completely self-contained, with refrigeration, testing equipment, and trained personnel, all established on islands that had been battlefields just weeks before. Can you imagine working in one of these war-torn areas? The sacrifice and demand that our soldiers and healthcare professionals went through was incredible.

The Human Cost and the Heroes Behind the Science

Behind every statistic was a human story, and none more important than that of Charles Drew himself. Despite his crucial contributions to the blood banking program that saved countless lives, Drew faced racial discrimination within the very system he helped create.

In January of 1942, the official U.S. policy stated it was "not deemed advisable to collect and mix Caucasian and Negro blood indiscriminately." Initially, the Army and Navy rejected blood from African-Americans entirely, later accepting it only if stored separately from that of whites.

Drew objected strongly to this unscientific policy. In 1942, he resigned in protest. In a 1944 letter, he called the segregation policy "a grievous mistake, a stupid error" for three reasons: "(1) No official department of the Federal Government should willfully humiliate its citizens; (2) There is no scientific basis for the order; and (3) They need the blood."

The irony was profound. The man who developed the blood banking systems that saved countless lives was told he could not donate to his own creation. As he noted in his 1944 Spingarn Medal acceptance speech: "One can say quite truthfully that on the battlefields nobody is very interested in where the plasma comes from when they are hurt."

The discriminatory blood segregation policy continued until December 1950, tragically after Drew's death in a car accident earlier that year.

The Peacetime Legacy

When the war ended, the blood banking infrastructure didn't disappear. It transformed civilian medicine. The American Red Cross opened its first nationwide civilian blood program in Rochester, New York. The techniques, equipment, and organizational methods developed during the war became the foundation for modern blood banking.

The mobile bloodmobiles that Drew developed for military use became community blood drives. The quality control measures developed under combat conditions became standard civilian safety protocols. The logistics networks created to supply forward military units became the template for hospital blood banks worldwide.

Lessons for Modern Phlebotomists

As phlebotomists working in today's healthcare environment, we are the direct inheritors of these wartime innovations. Every procedure we follow, every safety protocol we implement, and every quality standard we maintain traces its lineage back to the battlefield blood banks of World War II.

When we follow proper identification procedures, we're using protocols first developed to prevent transfusion reactions in combat casualties. When we maintain cold chain integrity, we're applying preservation techniques perfected under wartime conditions. The mobile blood drives we support today are direct descendants of Drew's wartime bloodmobiles.

The Enduring Revolution

World War II didn't just advance blood banking. It revolutionized the entire concept of transfusion medicine. The heroes of this revolution (Drew, and thousands of unnamed medical technicians, donors, and support personnel) created the foundation for every blood transfusion performed today.

Understanding this history helps us appreciate that our work as phlebotomists isn't just a job. It's participation in one of medicine's greatest success stories. Every tube we draw, every donor we serve, and every safety protocol we follow connects us to this remarkable legacy of innovation, dedication, and life-saving medical science.

The next time you're preparing for a blood draw, remember: you're not just collecting a sample. You're participating in a tradition forged on the battlefields of World War II, refined by heroes who understood that blood truly is the currency of life.

Related Posts and Information

overall rating: my rating: log in to rate