The Bloody Truth About Valentine's Day

This week we learn about Lupercalia, an ancient tradition with a blood sacrifice.

by Shanise Keith • February 17, 2026

Phlebotomy History, Phlebotomy News

Hello Friends,

Before we get to this week’s blog topic below, I have a couple of announcements for you. First, I will be reaching out to the two winners of the phlebotomy prize giveaway we had for Phlebotomists’ Recognition Week. So, if you participated please watch your email or Substack for a response from me in case you are one of the lucky two. Thank you so much for everyone who did participate, and to all of you for your continued support in reading this blog. It means a lot.

Secondly, I am very excited to let you all know that Dennis Ernst is now on Substack and he is busy writing all about his life and thoughts, and many more things. If you have known of the Center for Phlebotomy Education for more than the last five years then you have likely seen Dennis’s writing. He created this company many years ago, and has shaped generations of phlebotomists with his knowledge and expertise.

I am incredibly lucky to have had him as a mentor, and as a friend. Before I even personally knew him, I loved to read his newsletters about phlebotomy updates and important topics, but one of my favorite things to read was when Dennis would share stories about his life, which he called “From the Editors Desk.” He has a great talent for writing, and I have learned a lot from him as I try to continue his work, including this blog, Phlebotomy Today, which he started long ago.

Fortunately, he has not stopped writing, and anyone who wants to still hear from the previous Director can find him on his new Substack page, Stories from the Journey.

You can watch a video from his LinkedIn to hear him talk about it all here.

Okay, onto this week’s topic. I know I am a few days late for Valentine’s Day, but I didn’t want to interrupt the Order of Draw Series. So, with it only being a few days later I still think this topic is worth the detour — let’s talk about where this holiday actually came from.

Valentine’s Day is easy to take at face value — a holiday of hearts, flowers, and candy. But if you trace it back far enough, you find something that feels much more familiar to those of us who work in healthcare: blood, at the center of everything.

The origins of February 14th are older and stranger than most people realize, and they begin not with a saint or a greeting card, but with a Roman blood ritual that predates Christianity by centuries. As someone who thinks about blood professionally, I find this history genuinely fascinating. Long before modern science confirmed that blood is the key to understanding health and disease, ancient cultures already seemed to understand that blood was something powerful, something sacred, something worth paying attention to.

Lupercalia: Rome’s February Blood Festival

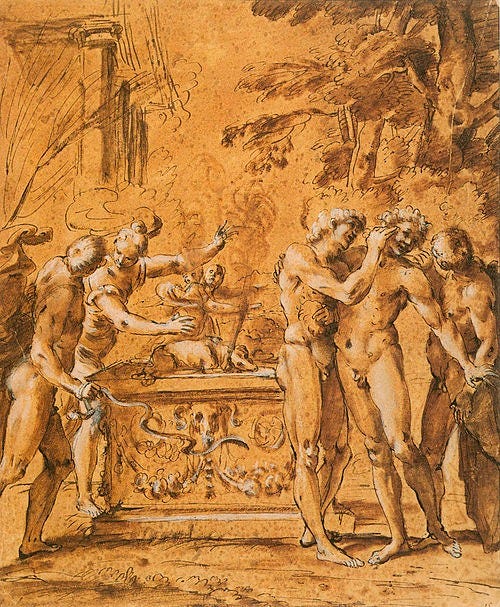

Every year from February 13th through the 15th, ancient Romans celebrated a festival called Lupercalia. It honored Lupercus, a god associated with fertility and agriculture, and it took place at the Lupercal — a sacred cave on the Palatine Hill in Rome where, according to legend, a she-wolf had nursed the founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus.

The festival was led by a group of priests called the Luperci, and it began with animal sacrifice. A goat and a dog were killed — the goat representing fertility, the dog representing purification. After the sacrifice, two young Luperci priests were brought to the altar, where their foreheads were smeared with the blood of the slain animals using a bloody knife. The blood was then wiped away with wool soaked in milk — and here is the part that history doesn’t quite explain: the ritual required the two young men to laugh while this was happening. Whether that laughter was ceremonial, nervous, or simply the ancient Roman equivalent of gallows humor, no one knows. Ancient sources record it as a requirement without fully explaining why.

After the sacrificial feast, the priests cut the hides of the animals into strips called februa — a word related to purification, and the root of the word February — and ran through the streets of Rome, striking people, particularly women, with them.

This was not considered an act of violence. Women ran toward the Luperci priests rather than away from them. Being struck by the februa was believed to confer fertility and protection during childbirth. In a time when maternal and infant mortality were devastating facts of daily life, that was no small thing. Blood wasn’t a symbol of danger in this ritual — it was a symbol of life itself, of the force that created and sustained it.

Later in the festival, a lottery of sorts was held in which young men and women were paired together. The pairing was meant to last through the year, and many, according to Roman accounts, ended in marriage.

It’s stories like these that make me wish I could time travel. To go back a thousands of years and witness an event like Lupercalia would be incredible… And maybe I could get an answer as to why the weird laughing was required.

From Blood Ritual to Saint’s Day

Lupercalia survived the rise of Christianity in Rome for longer than almost any other pagan festival — it was simply too popular and too deeply embedded in Roman culture to disappear easily. It wasn’t until the late 5th century AD, around 494 AD, that Pope Gelasius I finally moved to suppress it, declaring February 14th the Feast of Saint Valentine instead.

Saint Valentine himself is a historically murky figure. There were actually multiple martyrs named Valentine in early Christian tradition, and the Catholic Church has never been able to confirm which stories, if any, are historically accurate. The Church removed St. Valentine’s Day from its official calendar in 1969, acknowledging the uncertainty. What we do know is that according to popular legend, a priest named Valentine was executed on February 14th, around 269 AD, on orders from Emperor Claudius II — supposedly for performing Christian marriages in defiance of an imperial ban. He was beaten and beheaded, and later canonized.

So the holiday we associate with tenderness and romance began as a blood sacrifice and then absorbed the martyrdom of a saint who died violently for the sake of love. It has never been as soft as the greeting card industry would have you believe.

The romantic associations of Valentine’s Day didn’t emerge for another thousand years. The English poet Geoffrey Chaucer is the earliest known writer to connect February 14th specifically with courtly love, in a 1375 poem in which he wrote about birds choosing their mates.

For this was on Seynt Valentynes Day, Whan every foul cometh ther to chese his make, Of every kynde, that men thynke may; And that so huge a noyse gan they make That erthe and see, and tree, and every lake So ful was that unethe was there space For me to stonde, so ful was al the place.

In modern English: “For this was on Saint Valentine’s Day, when every bird of every type that one can imagine comes to choose his mate, and they made such a huge noise that the earth and sea and trees and every lake were so full of birds that there was hardly space for me to stand, so full was all the place.”

From there, the tradition of exchanging love tokens grew through the Middle Ages, formalized eventually into the cards and chocolates we recognize today. Scholars now believe that Chaucer may have essentially invented the Valentine’s Day-as-romance connection himself. There’s no documentation between the holiday and love prior to this poem, which makes it an even more remarkable footnote in history, and shows the power of the written words through time.

Seynt Valentyne, that are ful hy on-lofte, Thus syngen smale foules for thy sake: Now welcome, somer…

Modern English: “Saint Valentine, who art high aloft, thus small birds sing for thy sake: Now welcome, summer…”

What the Romans Understood That We Sometimes Forget

Lupercalia was built on something that, as phlebotomists, we encounter every day: the intuition that blood tells us something essential about life.

The Romans didn’t understand blood the way we do. They had no concept of blood types, no understanding of the coagulation cascade, no knowledge of what plasma and red cells actually are or do. Their relationship with blood was entirely experiential and symbolic — they observed that blood leaving the body meant something was wrong, that blood was associated with birth and with death, that it seemed to carry some vital property they couldn’t quite name.

It would take another 1,600 years after Lupercalia before William Harvey published his discovery that blood actually circulates — that the heart pumps it through the body in a closed loop, rather than it being continuously produced and consumed as the ancient Galenists (a name for Greek physicians of the era) believed. That 1628 discovery changed medicine forever and laid the groundwork for everything we do in a modern laboratory.

But the instinct was always there. Long before anyone understood the science, human beings across cultures recognized that blood was central to health, to life, to the forces that governed fertility and survival. They were right about that, even when they were entirely wrong about the mechanisms.

Today, when we draw a troponin level and help a physician diagnose a heart attack in real time, when we collect the CBC that catches a leukemia before symptoms become obvious, when we carefully follow the order of draw to protect the integrity of a specimen that might determine someone’s diagnosis — we are part of a tradition of taking blood seriously that stretches back further than we probably ever think about.

The Heart Then and Now

Medieval scholars and physicians believed the heart was the literal seat of emotion — the organ where love, grief, and passion physically resided. That’s why the heart became the enduring symbol of Valentine’s Day, even as science gradually revealed it to be a pump rather than a wellspring of feeling.

We now know, of course, that emotions are generated in the brain. But there’s something poetically true about the old association anyway. The heart is what drives the blood pressure that makes veins accessible. It’s the organ whose distress we measure when we collect troponin, BNP, and cardiac enzymes — tests that have saved countless lives by giving language to what used to be called, simply, a broken heart.

And as a small footnote that the phlebotomy community will appreciate: Phlebotomist Recognition Week falls in the week leading into Valentine’s Day. There’s something fitting about that. The people who work with blood every day — who understand its significance more concretely than almost anyone — sharing a week with a holiday that has, from its very origins, recognized the same thing.

Related Posts and Information

overall rating: my rating: log in to rate